Lightning Photography Guide (2024)

My ultimate guide to photographing lightning

Hey everyone and welcome to my ultimate guide on how to photograph lightning. Here you will find an in-depth deep dive into the knowledge and techniques you'll need to photograph lightning effectively. After chasing storms and photographing lightning for over a decade, my hope is that beginners and experts alike will find this lightning photography guide useful.

I'll demystify the exposure triangle when it comes to how to effectively photograph lightning before diving into the settings I use as well as how I approach different scenarios.

I'll also discuss my post processing and development techniques and show you how I make my lightning photos really pop. Whether you're a seasoned pro or a beginner starting out on your lightning photography journey, you'll hopefully learn something useful or glean an unthought tidbit of information.

my lightning photography journey

Any in-depth guide to lightning photography has to start with at least a little bit of history of the author's experience. If anything, it shows he might know what he’s talking about ( admittedly debatable). Feel free to skip over this bit if you wish (because zzz).

Though I’ve been chasing storms since 2007, I didn’t exhibit a ‘real’ interest in lightning photography until 2013. The image below represents my earliest attempt. It was captured on a now old and battered Canon Ixus perched precariously on a groyne somewhere along Brighton seafront.

Yeah I know its terrible but I loved it and from that moment on I was hooked.

My History of Lightning Photography

A couple of years after that first lightning photograph, I invested in my first DSLR - an entry level Canon 700D - and started chasing storms along the south coast and home counties during the summer months.

They were usually 'high-based', meaning the base of the storm cloud was elevated higher in the atmosphere. This was a requirement if they were to ever make the Channel crossing as sea surface temperatures would ‘cool the fuel’ a storm needs. (The difference between a surface-based storm and an elevated storm and their subsequent ability to make it across a large body of water is a topic for another discussion).

Elevated storms migrating across the Channel taken with the Canon 700D. Love those undulating bases.

After chasing these French imports for a year or so, my ambition grew to investing in a Canon 80D which I still own today. After acquired some extra lenses, I found myself back in Tornado Alley again the following year following a 5 year hiatus. Here I met Dave and Arron who would subsequently go on to form See Nature’s Fury.

Though 2017 was a poor season overall, it seriously kickstarted my drive to photograph storms and in particular, lightning.

A month after returning home to Brighton from that tour, one of the greatest lightning displays I’ve ever witnessed passed directly over my apartment.

Huge lightning bolts and rainfall from the MCS that crossed Brighton in 2017.

big lightning

At that time I was fortunate enough to be living on the top floor of an apartment block. It had uninterrupted views up and down the coast and out over the English Channel. After studying the forecast for that evening, it was merely a case of sitting on my balcony in the warm summer air and waiting for what would be the mother of all MCS’s to arrive.

As the complex drew nearer, lightning activity appeared to be focused by the presence of a wind farm 8 miles out to sea. Some unbelievably crazy lightning strikes would hit the turbines. To this day I’ve still not seen better lightning than that evening and I would say that this was the moment that arguably cemented my love of lightning photography.

The presence of the offshore wind farm appeared to focus the lightning as bolts became increasingly CG.

the hunt begins

Since that evening on the south coast, I've been fortunate enough to photograph several storm systems that have migrated across the Channel from the continent. I have been on the hunt ever since and to chase down and witness lightning has become an addiction. This addiction has led to a persistent honing and development of my photography skills and cemented my preferred method of capturing lightning which has reaped some great rewards. Not actual rewards I hasten to add, but personal ones although I was a finalist for the RMetS Weather Photo of the Year for 2019.

Of all the aspects of chasing and photographing storms, lightning holds a unique fascination for me with its transient, ethereal nature. Every bolt is different and capturing any one of them is like, well…capturing lightning in a bottle.

After a decade of photographing lightning, I want to share with you the knowledge I've built up over those years by writing this in-depth guide to lightning photography.

What is lightning anyway?

Lightning is the resulting spark that occurs when opposing charged regions between cloud and ground break down. The key word here I guess is ‘spark’ as there is a common misconception that lightning can be separated into 2 distinct types - forked lightning and sheet lightning. Truth is, there is no such thing as 'sheet' lightning. What some might call sheet lightning is just forked lightning that occurs within the cloud or behind curtains of rain. What you’re actually seeing then are those areas being lit up from behind by 'forked' lightning. Though this might seem basic to some and shouldn’t need explaining, there is an important consideration to be had here; If you’re out chasing storms and all you can see is ‘sheet’ lightning, then you might want to consider your positioning on the storm. More on this later.

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PHOTOGRAPHING LIGHTNING

Lightning can be inherently tricky to photograph effectively.

It's transient and unpredictable, instantaneous, intensely bright, occurs in a split second and you’ve no idea when or where it will strike!

Its intensity can vary from bolt to bolt depending on its distance from the observer, how much dust and haze there is in the atmosphere and how much cloud and precip might be surrounding it as well as different storm dynamics and geographical location that can affect the current.

But once you grasp the principle of how to capture it and understand this variability, before long, photographing lightning becomes quite straightforward.

EQUIPMENT YOU WILL NEED

My comprehensive guide to lightning photography assumes you are using:

- DSLR camera

- Tripod

- Remote Shutter

I also reference some extra third party equipment throughout this guide, but they're not essential.

Now, with this in mind, I hasten to add that none of the above is strictly necessary - after all, my first lightning photography was captured on a pocket camera - though there is a technique I delve into later that absolutely requires a tripod. What’s important is that your camera allows you control over the different elements of the exposure triangle.

(I’m sure if I’d known more about that back then, I might have taken a better photo.)

You could, therefore, take lightning photos perfectly well with your phone as long as your phone allows you to manually control the camera’s exposure settings.

Which leads me nicely to…

the exposure triangle

I'll let ChatGPT briefly explain this...

"The exposure triangle is a fundamental concept in photography that explains how three key settings—aperture, shutter speed, and ISO—work together to control the exposure of your photograph. Understanding and mastering these elements is crucial for creating well-exposed images under different lighting conditions.

Aperture (aka f-stop) refers to the size of the opening in your lens through which light enters the camera. A larger aperture (small f-stop number like f/2.8) allows more light to hit the sensor, resulting in a brighter image. A smaller aperture (large f-stop number like f/16) lets in less light, making the image darker.

Shutter speed is the amount of time the camera's shutter is open, allowing light to hit the sensor.

ISO measures the sensitivity of your camera’s sensor to light. A lower ISO (like 100) makes the sensor less sensitive to light, resulting in a darker image. A higher ISO (like 1600) increases the sensor's sensitivity, making the image brighter. While increasing ISO allows you to shoot in lower light conditions, it also introduces noise or grain into the image, which can reduce image quality. It's usually best to keep ISO as low as possible, only raising it when necessary.

These three elements are interconnected. Changing one affects the other two, so you need to balance them to get the correct exposure for your image."

PRINCIPLES OF PHOTOGRAPHING LIGHTNING

When I’m photographing any lightning scene, I’m obviously expecting there to be a big bright flash in it. This means that I essentially need to consider and expose for 2 different lighting elements in one photograph. These are the overall ambient light in the scene itself but also the bright flash of the lightning.

Which then should I prioritise?

Consider this first: photographing lightning is, unsurprisingly, fundamentaly like flash photography but on a much bigger scale. However, whereas in flash photography the light from the flash gun can be controlled, measured and exposed for accordingly, this obviously cannot be done with a lightning bolt. Also, the light from a flash gun comes from behind the camera, whereas in lightning photography you're trying to capture the source of the flash itself occuring in front of the camera.

Therefore, I prioritise my aperture setting first and foremost to expose for the bright flash of the lightning bolt.

Secondly, I adjust my shutter speed as a consequence of my aperture setting in order to correctly expose for the ambient light of the environment.

Thirdly, I adjust my ISO depending on certain conditions which I’ll get into later but I almost always try and shoot with an ISO of 100.

ANALOGY

To further help you understand why I prioritise my aperture setting, here is a simple analogy for you to help you get to grips with photographing lightning. Hopefully it will help you understand why it is your aperture that matters over the other two.

Imagine you’re photographing a big dark storm cloud and you’re poised, waiting for that lightning to strike. The length of time your shutter speed is open for could be 1/100th of a second or it could be 10 seconds.

The lightning flash occurs in 1/1000th of a second.

This means that, regardless of shutter speed, the amount of light from the lightning flash that hits the sensor will be the same in both instances regardless of how long you hold the shutter open for.

Therefore, in order to correctly expose for the brightness of the flash, it is my aperture setting that dictates how bright or how dim that flash will appear in my image.

With my aperture set to expose for the lightning, I then rely on my shutter speed - as a corollary to my aperture - to expose for the ambient light in the scene. The length of my shutter speed should be set accordingly to keep the exposure triangle balanced.

ILLUSTRATE

Let's see if I can’t illustrate all of this better with a bunch of crude diagrams.

For the sake of argument, imagine both images below were shot with my lens’ aperture open at f/8. The image on the left was shot with a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second. The image on the right was shot with a shutter speed of 1/10th of a second. The lightning flash occurred in 1/1000th of a second.

A shorter shutter speed means less ambient light will hit the sensor leading to an underexposed image.

A longer shutter speed allows more ambient light to hit the sensor and produce a better exposed image.

Note how in both images, the brightness of the lightning is the same but the ambient light is brighter in the image on the right due to the longer shutter speed which allowed the sensor to absorb more ambient light.

!Remember - the speed of the lightning strike is too fast to be affected by the choice of shutter speed!

In order to keep my entire image correctly exposed, I personally find the best way to determine what my shutter speed should be is with the camera’s histogram. I always shoot in manual mode. With my aperture set, I simply dial in my shutter speed until I get the histogram balanced to how I want it. I have a tendency to ETTR (Expose To The Right) to ensure my sensor is getting as much ambient light information as possible.

Obviously, it's also important to remember that longer shutter speeds introduces a risk of motion blur in your image. This can either be from slight movements of the camera itself or from vegetation such as trees and grass being blown by the wind. In order to compensate, or if I feel I’m ‘dragging’ my shutter too much, then I might increase my ISO allowing me to use a faster shutter speed.

I do not touch my aperture.

Of course, you might want everything in your scene to be as sharp as possible at all times. How you ensure this is outlined in some of the lightning capture methods discussed below.

For now, the information you’ve learned above should be a great jumping off point.

DELVING DEEPER INTO LIGHTNING PHOTOGRAPHY

Now that you’re familiar with the principle of how to photograph lightning, let's delve a little deeper.

As I previously mentioned, whereas in flash photography you can control and measure the amount of light emitted from the flash gun, and set your exposure settings accordingly, this is obviously impossible with a lightning bolt.

Now add in distance, duration, storm mode, time of day, atmospheric conditions such as haze and dust, precip from the storm itself, the amount of current running through the lightning channel and what the storm itself is doing (i.e. is it producing smooth laminar bolts out of the mid levels or monster forks out of the anvil?); all of these affect the variability of the brightness of a lightning bolt either in isolation or in combination.

To compound matters further, not all lightning strikes are created equal either. Some are brighter than others, whilst some persist for longer than others. If all lightning strikes lasted 1/1000th of a second and were all of equal brightness then photographing lightning would be a lot easier.

As daunting as all that sounds, gauging this amount of variability comes with experience. At the end of the day, it simply comes down to opening up or closing down your aperture by however many stops necessary.

Elevated bases and low tops were noted from this MCS which was likely more castallanus than cumulonimbus. The elevated base of the storm means there are more ice particulates which leads to increased electrification. Note the dimness of the bolt due to distance, haze and precip.

time for another diagram

Whereas 1/1000th of a second might sound very quick, a lightning strike can sometimes be even half that duration, and therefore appear dimmer in your photography, or many times that duration, appearing brighter.

Again, imagine your aperture is open at f/8 and, for the sake of argument, your shutter speed is set to 1/50th second.

Assuming equal current across both strikes, a lightning strike that lasts 1/1000th second will not render the same result as a strike that lasts 1/100th of a second, regardless of shutter speed. Here, the brightness of the lightning is persisting for longer and is therefore being exposed to your camera’s sensor for longer. It might only be fractionally longer in the grand scheme of things, but the difference can be noticeable, especially during the darker hours.

A lightning strike that lasts fractionally longer will render brighter in your photography.

A lightning strike that lasts fractionally shorter will appear dimmer in your photograph.

I hasten to add that lightning tends not to vary so wildly from strike to strike within a single storm. Obviously there will always be some fluctuations especially as a storm's environment evolves, but such wild variations occur more on the synoptic scale from environment to environment rather than the mesoscale. For example, a supercell in New Mexico is likely shooting out super quick positive CGs compared to the lengthy strobed anvil rippers from that MCS raging across southern Oklahoma.

If you want to become a serious lightning photographer, then studying storm modes and storm morphology can reap dividends. Again, at the end of the day, how lightning appears in your photography is all down to your choice of aperture.

DIFFERENCES

To illustrate how certain atmospheric conditions, coupled with different 'kinds' of lightning, can affect your exposure, take a look at these two photos below which were taken several moments apart. They’re of the Morton, TX supercell in 2022.

Note how in the image on the left, the lightning is perfectly exposed but the lightning in the image on the right is starting to blow out and is therefore overexposed.

Why is this?

This is due to a combination of three separate factors:

- The lightning in the image on the right is much closer. (It was shot at 24mm which distorts the perspective so the bolt is actually a lot closer than it appears in the photo).

- The lightning in the image on the left is not only more distant but is also partially obscured by the dust this supercell was infamous for. As the majority of the lightning was striking in and around close to the updraft, I adjusted my exposure settings for this.

- The lightning in the image on the right has a lot more current running through it. See how it has multiple forks emanating from it compared to the singular bolts in the image on the left. It is more powerful and therefore brighter than the more ‘regular’ bolts the storm was throwing out. There is also less dust obscuring the bolt due to its closer proximity.

METHODS

Now that I’ve explained the principles, let’s look at the variety of methods you can try when it comes to photographing lightning.

Which one you pursue may well come down to aesthetic choice above all else.

LIGHTNING TRIGGER

Arguably the most popular choice if you're a dedicated lightning photographer is to use a lightning trigger. A lightning trigger is a small device that plugs into your camera and slots into the hotshoe. It senses sudden changes in light levels and tells the camera to take a shot when it detects a strike. This sensitivity can be adjusted so it can detect even faint distant strikes but a degree of finesse is sometimes needed to gauge that adjustment. I've watched as the trigger is sometimes prone to firing off random 'empty' shots, especially during daylight hours. Other times I’ve seen it miss strikes completely.

I hasten to add that I myself don't own a lightning trigger but the issues mentioned are ones I've witnessed in the field with fellow chasers. On one occasion the trigger / camera pipeline simply wasn't quick enough to react. (Again, I'm looking at you New Mexico.) The Hagerman supercell of July 2019 fired out bolts so quickly that the trigger simply couldn't react in time. I even shot video of this storm and half the bolts didn't even show up. Though this isn't really a 'fault' per se of the trigger, it does highlight limitations in this method though not every storm is going to throw out bolts as fast as the Hagerman one.

Just look at how vibrant and colourful the bolt is from this lightning shot from the Hagerman, NM supercell. It struck so quickly that the lightning trigger couldn't react in time. This shot was taken using my preferred method of timelapsing and you can view this image over at my 2019 storms gallery.

HIPFIRE METHOD

The good old hipfire method of shooting and hoping does make me laugh as photographers crouch in front of their cameras with the shutter ratcheting away like an AK-47. Its arguably the best method though if image sharpness and fidelity are your primary concern. There’s certainly no denying the results when you capture that bolt.

Basically, you set your camera to high speed continuous shooting mode. When you think there’s going to be a strike, simply hold down the shutter button until there is one. Conversely, you wait until a strike occurs and you pray you have ninja reflexes (not a hope if you’re shooting in New Mexico).

If lightning is frequent and consistent enough then you can hazard a guess as to when a strike will occur. Then you just fire away until one does. Sometimes, on rare occasions, the storm might be generous enough to give you a little precursor to a ground strike by first rippling through the cloud deck. You might even get one of those super-charged positive strikes that discharge multiple times down the same channel. In this instance you'll have plenty of reaction time to open the shutter.

If you use this method then I imagine you’re probably opting for a faster shutter speed so as to retain image sharpness. You'll definitely have to use a fast shutter speed if shooting hand-held. Storms by their nature tend to generate windy environments so a longer exposure will mean wind-blown elements in your scene are inevitably going to be blurred. The downside to faster shutter speeds is that travelling bolts can be fragmented. You can always combine those shots later in post though.

Some modern smartphones can work well in this example as they now shoot ‘motion’ photos. Motion photos are short video sequences that capture a few seconds of action before and after the shutter is pressed. Simply press the shutter button when you see a lightning bolt and Bob’s your uncle - the lightning will hopefully have been caught in one of the ‘before’ shots.

Admittedly the only time I've ever used the hipfire method to capture lightning and even then it was unintentional. I was hunkered down behind the car sheltering out of the wind and rain to capture an ordinary shot of the storm. You can view this image over at my Storms USA 2022 Gallery.

TIMELAPSE METHOD

Timelapse is when you take a series of photos at a set interval for a certain duration. For example, when I'm timelapsing a storm I'll take a single shot every second until I've taken about 300-400 photos. This gives me roughly 10 seconds of footage when played back at 30fps. To achieve this, your camera needs an intervalometer function. If it doesn't have one then you can attach a 3rd party intervalometer device such as this one from LRTimelapse.

Timelapse has always been my preferred method ever since sitting on my balcony back in 2017. I got fed up with forgetting to press the remote shutter after each exposure. Simply dial in your exposure settings, set up the lapse, then sit back and enjoy the show. The downside of this method though is the number of bolts that can fall between exposures. Both my Canon R6 and 80D only have a minimum of a 1 second interval meaning that it will wait a whole second after the last shot is taken before the next shot is taken.

Do you have any idea how annoying it is the amount of bolts I’ve seen fall within that 1 second?

Third party timelapse devices like the aforementioned one from LRTimelapse can overcome this by allowing you to use faster intervals. Admittedly this is extra cost on top of what is likely to be an already expensive outlay. I’d recommend checking it out however if you’re serious about your lightning photography.

Don't worry if your camera doesn't have a timelapse function or your budget doesn't extend to buying an additional controller as there is a redneck solution you might want to try. Get hold of a cheap remote shutter release (I use this one), dial in a longer exposure setting and simply lock down the button on the remote shutter. This has the advantage of there being no intervals between shots so you won't miss out on that thundery magic. The downside however is that you're forced into using longer shutter speeds to slow down your capture rate. If your camera doesn't have an intervalometer function then it likely has a smaller image buffer. If it has a smaller image buffer then less photos can be taken before that buffer becomes overloaded regardless of memory card capacity.

I much prefer the timelapse method of capturing lightning as not only can I capture vibrant images such as this, but I can also sit back and watch the show unfold.

LONG EXPOSURE

I thought I'd give this its own section though you'll probably combine this method when timelapsing storms at night. To clarify, by long exposure I'm referring to a shutter speed of about 5 - 10 seconds or more.

Traditionally, photographers generally like to use longer exposures as it allows you to capture multiple bolts in a single exposure to create the barrage effect in-camera (as opposed to stacking in post). As your aperture will be set to capture the brief, bright flash of the lightning as described previously, the shutter can be held open for longer to expose for the much darker ambient light.

Shooting longer exposures comes with its own unique problem however. Take a close look at the following image…

The inherent problem of using longer exposures to capture lightning; as the cloud moves and evolves between strikes - even if just a couple of seconds apart - the same area of cloud can be illuminated multiple times creating a multiple exposure effect.

the long exposure 'problem'

Notice the pattern of the cloud across the middle of the screen and how it appears to have 'doubled up'. This occurs due to the evolution of the cloud during the length of the exposure. In this instance, at the beginning of the exposure there was an intercloud lightning strike which lit up certain areas of the storm. This was followed by a CG strike at the end of the exposure which illuminated those same areas again. The cloud has obviously evolved in between lightning strikes and thus you get a kind of stacked, double exposure effect.

This is often an inherent issue when you're stood some distance from the storm with the full storm in view. Multiple lightning strikes caught within a long exposure can inevitably 'cross contaminate' the same areas, illuminating them up several times.

Longer exposures also increase the risk of camera shake from the inflow / outflow regions of a storm. That same wind field will also inevitably blur any grasses or trees etc in the foreground.

CONSIDERATIONS

In addition to all of the above, if it wasn't already lengthy enough, there are a couple of other things that are worth considering.

DURATION

Sometimes the duration of a lightning strike can be too long. As I mentioned previously, the lightning might ripple through the cloud first before emerging from the storm. If you’re using a lightning trigger for example, it will detect that initial increase in light through the cloud and open the shutter before the bolt emerges from the cloud. If it's the case of a bolt travelling a long distance, then the trigger might catch the start of the bolt but not the end.

You can overcome this by setting a delay timer on the trigger. This will cause it to wait a fraction of a second before firing. Alternatively, you can just make sure you use a longer exposure, the pros and cons of which I’ve already outlined. If I remember correctly though, the trigger can also keep firing off multiple shots for the duration of the strike as long as it's still detecting light level changes. If the strike lasts longer than than your shutter speed then the lightning trigger will still detect the light and thus fire again. You can then combine these separate images in post.

STORAGE

This is a consideration more for the hipfire method. In order to capture as many frames as possible, you’ll preferably need a camera with a high fps rate. My Canon R6 can shoot at a burst rate of 20fps which is more than enough. The major issue here though comes down to how much storage you have. You’ll obviously need a fast storage card to deal with all that continuous throughput and plenty of cards in reserve because all those 'empty' shots will soon mount up.

If you opt for the timelapse method, then you will definitely need plenty of fast storage as even taking a photo every second can overwhelm the write speed of some slower cards.

Summertime 'airmass' or 'pulse' thunderstorms over the Sussex Weald

MY CAMERA SETTINGS AND MY APPROACH

What I find helps me in my choice of aperture is the knowledge that, with the brightness of almost a trillion lumens and a temperature 5 times hotter than the surface of the sun, a lightning bolt just isn’t something I should be trying to ‘correctly’ expose for, so why even try?

Assuming its not obscured by too much haze or precip, lightning will more often than not be the brightest element in your scene.

To be clear, you can correctly expose for a lightning bolt so that it isn’t overexposed. You do so by choosing a very fast shutter speed - faster than 1/1000th sec - and by closing your aperture right down. You would then either rely on the hipfire or lightning trigger methods mentioned above and cross your fingers.

However, not only would the ambient light from the rest of the scene become so badly underexposed as to become unrecoverable if you tried this, the lightning bolt itself inevitably loses all of its impact and lustre.

They end up looking translucent and ghostly, which may be the aesthetic choice you’re aiming for, but then you miss all the stunning colours in the aura and in the branches.

It is that aura and those colours that I essentially expose for.

COLOUR, AURA & BRANCHES

To me, a successful lightning photo reveals the central bolt to be bright with a colourful, vibrant aura and the branches to be all manner of blues, reds and violets. It has impact.

My approach then centres around being able to hold my chosen aperture open for as long as possible to maximise my chances of catching a strike whilst simultaeneously trying not to overexpose the sensor to too much ambient light.

Equally, I don’t want my shutter held open for too long else I risk losing image sharpness by introducing too much motion blur.

bolt thrower

f/11

1/2 sec

ISO100

In this shot, I'm essentially exposing for the sunlight behind the rain curtains in the lower half of the image. The 1/2 second exposure allows the sensor to absorb enough light from shaded areas so the information can be recovered in post. The bolt remains beautiful, crispy and colourful. You can view this image over at my 2022 Storm Gallery

PROXIMITY AND OBSERVATION

Knowing then that an unobscured bolt will be too bright to expose for, it's all about minimising that overexposure so as to effectively capture the aura of the strike and the colours in the branches.

During daylight hours I like to keep my aperture within the ‘sharp’ range - anywhere from f/7.1 to f/16. I adjust this value depending on the environmental factors I outlined above; how close or distant the lightning is striking (and therefore how bright it is likely to be), and/or how much haze or precip is obscuring the lightning etc, stepping down the aperture the closer the storm - and therefore the lightning - gets.

This aperture range serves a number of purposes. Not only does it help minimise the over exposure of the lightning and thus bring out the colours, it also allows me more freedom to 'drag' the shutter.

What also helps in this process is my use of a polarizer which not only helps bring out those colours but because it reduces light entering the lens by a stop or 2, it allows me to be able to drag the shutter just that little bit more.

It's then a question of trade off between how long I can drag the shutter whilst maintaining image sharpness.

It's also equally important to pay attention to what the storm is doing. What kind of bolts is it throwing out? How much current is there? Are the bolts positive or negative, super quick or strobing, CG or intercloud? All of these points must factor into my choice of aperture.

comin' ta getcha

f/16

1/4 sec

ISO100

Even with a small aperture, the main bolt is beginning to overexpose whilst the branches are all perfectly colourful, crispy and correctly exposed. The storm is almost upon us in this shot so the lightning is pretty close, hence its more intense appearance. This was also shot in New Mexico though where those positive anvil CGs are just something else! You can view this image over at my 2019 Storm Gallery.

NIGHT AND DAY

You'd be forgiven for thinking that, as the energy emitted by lightning is more or less the same regardless of the time of day, then the brightness is the same and therefore the same aperture can be used whether day or night.

Not so.

The reason for this is something I intend to explore further, but which I think essentially comes down to the additive nature of sunlight with increased ambient light levels in the scene 'adding' to the brightness of the lightning.

The aperture setting I choose for daytime lightning therefore will not be the same for lightning striking at night, or even in the twilight hours.

Bear this in mind as a storm grows closer - the scene inevitably becomes more overcast and ambient light levels drop. Rather than extend my shutter speed and increase the risk of motion blur, then I might be tempted to open up the aperture a little more, usually within the f/7.1 - f/11 range, again dependent on the proximity of the storm. Or, if it's really overcast, then I’ll cautiously bump up the ISO instead. I’m not too concerned that the scene might look a little underexposed as the shutter speed will still have been open long enough for the sensor to have absorbed enough ambient light that I can recover in post.

At night, I open the aperture all the way up and only now do I really bump up the ISO, again according to the storm’s distance, amount of haze etc. This is when I have to be most careful as it is all too easy to overexpose and blow out the lightning. Just a couple of f-stops can make the difference between luminous, colourful bolts and a fully blown out image.

During twilight, night time hours I can really drag the shutter, holding it open for about 5 - 10 seconds or more. I’m not worried about motion blur here either because there won't be enough ambient light to illuminate it anyway and as lightning acts as a flash, it will illuminate the scene into sharp relief.

Fourplay

f/7.1

15 sec

ISO100

The trailing stratiform area of an MCS, like this one over Brady, TX, is one of the best locations to capture lightning. My wide angle lens gives the impression the storm is quite distant when in fact it was very close, reflected in my choice of exposure settings.

levelland

f/4.5

10 sec

ISO400

Care needs to be taken when photographing lightning at night as it's easy for bright areas of cloud or precip to become overexposed. Although the storm was almost on top of us, the lightning was still fairly dim - obscured by the thick red dust - hence the wide open aperture and increased ISO. You can view this image over at my 2022 Storm Gallery.

fast or higher?

Only under certain conditions will I use a 'fast' lens with an f stop of 2.8 or more. Occassions for this are when the storm is distant and / or in a very muggy environment where the illuminating effects of the lightning are diminished.

In the image below taken near Dodge, KS, I used a 50mm focal length wide open at f/4. Sadly it was nowhere near enough to capture the lightning and cloud flashes which were muted by humidity and distance. Even with the ISO bumped up to 1600, its still not enough; I had to do a lot of post-processing recovery in Lightroom. A real shame because its a very atmospheric image.

Given the choice of using a faster lens over increasing my ISO, I will always opt for a faster lens.

dodge

f/4

10 sec

ISO1600

An occassion where I wished I'd used a faster lens was this distant storm near Dodge, KS. Even with the aperture wide open at f/4, the intracloud lightning is barely visible; hidden within the cloud and behind a thick soupy haze. Even with a high ISO, the exposure had to be cranked right up in post resulting in a very noisy image. You can view this image over at my 2022 Storm Gallery

The perils of using a fast lens in combination with increasing the ISO however are evident in this pair of images below. A tricky combination of distance, changing light conditions and lightning that was striking in and around the precip core made for a storm that was difficult to expose for. For the most part, my exposure settings of f/2.8 at ISO640 worked well for exposing for the structure of the storm illuminated by the lightning hidden deep within the cloud and the forward flank core. But as soon as the lightning struck immediately outside of the precip, it's overexposed. In these instances, lowering the ISO to 200-400 would probably have been safer. The balance is a precarious one.

Night time lightning is inherently the trickiest to expose for.

Whereas for daytime lightning, a good starting point is simply to adjust your exposure settings to expose for the brightest element in the scene (the brilliant whites of cloud tops or the brightest part of the sky) you have no such luxury in the dark. If there's still twilight visible, as in the photo on the left below, then start there.

CONCLUSION

I hope I haven't waffled too much to get to this point but in conclusion, with my choice of aperture I aim to have the lightning slightly underexposed in an effort to retain as much colour detail as possible in the branches and in the overall glow. I still want the core bolt to be bright but not so bright that the glow blows out and becomes overexposed. Closing the aperture down enables me to use longer shutter speeds which serves both to help increase my chances of catching a bolt and allows the sensor to absorb more ambient light that would otherwise be restricted by using a smaller aperture.

IN THE FIELD

On top of everything else, you also have to consider the effects the environment will have on you.

First of all, and this shouldn't need saying, photographing lightning is inherently dangerous. Hands down it is the most hazardous aspect of chasing a storm. NEVER stand under or near tall objects or trees if a storm is directly overhead. Do I even need to state this?! Don't make yourself the tallest object either, not that that matters as lightning can quite happily avoid tall structures and certainly don't stand on top of a hill! Even if you're some distance from the storm, lightning can reach out and grab ya, especially if the storm is raining down those silly bolts out of the anvil.

elements

Storms can inherently be wet and windy affairs. Be aware then that raindrops will inevitably make it onto your lens. Attaching a lens hood can help mitigate this but can transform your camera into a sail during windier conditions. This is where you need to make sure your camera is securely attached to the tripod head. There should be little to no give and the tripod itself should be sturdy. I’ll usually splay the tripod legs out one notch further with 2 of those legs facing downwind. Ideally, you’d have the camera as low to the ground as possible by shortening the legs and splaying them out. However, this is rarely practical when it comes to your composition. Never extend the centre column of your tripod if it has one - that's just asking for trouble.

Pop up storms that form on hot and humid summer days can be the exception. Around them the air often feels “close” and “still”. This is due to the lack of wind to ‘mix out’ the atmosphere. Wind and rain from these storms tends to exist solely in the vicinity of the storm.

Being stood out in the open exposes you and your camera to the elements. Not only do you have to shelter from the wind and the rain but also that most dangerous thing you’re trying to photograph – lightning.

positioning

I find positioning myself in the right place around a storm provides the biggest hurdle to overcome. Good road networks are essential for effective positioning which is why chasing storms in the UK is so poor. Having to factor in an interesting foreground with meaningful composition around where lightning is most likely to occur is an incredibly difficult task and often comes down to luck.

‘Knowing’ a storm can help in this regard. An educated guess can be made as to the direction the storm is heading. The region of the storm where lightning is most likely to occur can also be guessed at. Then you just hope the storm is slow moving and long lasting enough for you to be able to position yourself accordingly. You just have to hope there’s some visual interest when you get there.

If you're opting to chase storms in the UK, I find that the best strategy is not to chase per se. Instead I position myself beforehand where I have a composition in mind in an area where storms are forecast to track over. Rarely will a storm be so kind but this is when knowing where storms occur most often and then getting to know that area pays dividends. For example, MCSs in the summer months frequently make their way over from the continent to the southern shores of the UK. They then track north east in the direction of Kent and East Anglia. CAMs (Convection Allowing Models) are so good now that they can predict roughly when and where a storm is likely to occur. You can and should use this guidance to your benefit.

location knowledge

Coastal areas are a great option as there’s always foreground and compositional interest due to the rugged nature of the coastline. The UK certainly has a lot of it so positioning shouldn’t be too much of an issue. Failing that, bodies of water such as lakes and reservoirs where reflections can compensate for any lack of visual interest. Mountainous areas can certainly offer arguably the most dramatic views but navigating around them is problematic and positioning can be fraught with risk.

Winding country roads (assuming you can find somewhere in the UK to pull over) are also relatively easy to come by and who doesn’t love an ‘end of the road’ shot? Navigating them though can often be a frustrating experience. South eastern counties, where trees and hedgerows are an absolute blight on visibility and accessibility, make for horrendous chase country. The same can be said for the hills and forests east of I35 in the US. With this in mind, which probably only applies to chasing in the UK, smaller cars allow far greater accessibility when navigating around country roads. Being able to pullover in front of a farmer's gate is a lot easier in a hatchback and doesn't block the road like a 4x4 would or a van.

radar and satellite

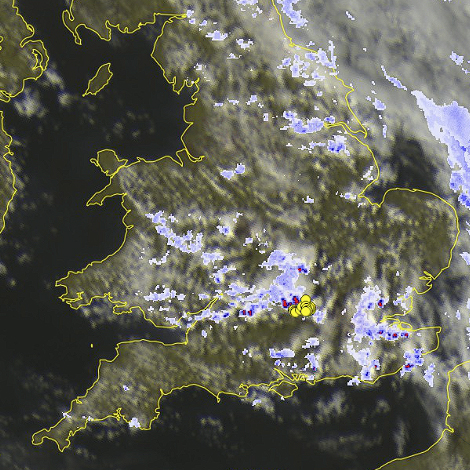

Storm modes and chase strategies, especially around the UK, are probably outside the scope of this blog. However, there is a quick way in which you can tell where lightning is occuring most around a storm. Online radar tools from Meteogroup and Netweather can be a huge benefit in helping you navigate yourself into the best position around a storm as they indicate where lightning is in relation to the precip.

In the image above, you can clearly see a tight cluster of sferics on the leading edge of a couple of thunderstorms pushing south east towards Reading. If you look closely you can see that the strikes are occuring in front of the darker coloured returns. This indicates they're falling slightly ahead of the updraft column and maybe photogenic. Best photography location in this instance looks to be to the south or south west out of the rain where the skies are clearer.

The downside is that they're not realtime, with updates coming every 10-15 minutes, so there is a discrepency between the position of the sferic and the radar return of the precip. If this is an issue then you can always refer to either Lightningmaps or Blitzortung which show lightning 'sferics' in realtime. Neither has radar or satellite overlay but it should be fairly straight forward to cross reference.

thank you

If you have made it this far; Thank You!

If you have any questions or feel you have have anything to add, then please contact me. The best way to do this is to drop me a message over on my Facebook page. Your feedback and interaction is always welcomed and appreciated. Of course, if you have any lightning photos to share then please do so.

CHEERS!

Comments are closed.